Large Parks

Julia Czerniak and George Hargreaves

Princeton Architectural Press | 2007

“In Large Parks, Julia Czerniak and George Hargreaves present eight essays by leading scholars and practitioners that engage large urban parks in depth as complex cultural spaces, where key issues of landscape discourse, ecological challenges, social history, urban relations, and place-making are writ large.”

Princeton Architectural Press

“While focused on a narrower topic, this book shares many traits with the reader on landscape urbanism, mainly the view that landscape can help the city; the large scale of the urban park can do more than provide recreation, it can be an important public and ecological place for the city.”

John Hill, A Daily Dose of Architecture

Preface

The sustained interest in landscape over the last two decades is at once remarkable and obvious, given the impact of its study and built work. Publications such as this reflect and generate continued and thoughtful attention. Large Parks follows The Landscape Urbanism Reader (2006) and Recovering Landscape (1999) as the third in a series of publications from Princeton Architectural Press that engage and advance this topic.

The essays, commentary, and graphic material contained within Large Parks were developed through a number of events. One of these was a conference held at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design in April 2003, where the topics of the city, ecology, process and place, the public,and site history were used to frame and launch a discussion about the impact and significance of size relative to the planning, design, and management of parks, past and future. Many of the ideas and speculations that resulted from this conference informed the subsequent development of the essays that follow. Along with this conference was an exhibition of large-park case studies by GSD students that provided thoughtful and innovative material that supplemented the discussion. Encouraged by the interest generated by this material, the idea of a publication about large parks was born. The subsequent provocative development of the material – through colloquia, meetings, discussions, and debates – is a testament to the topic’s timeliness and relevance for the design disciplines today.

Foreword

James Corner

For most of us, large parks conjure up marvelously visceral images of large-scale green open space, replete with forests, allée, bosques, meadows, lawns, lakes, streams, bridges, paths, trails, promenades, and innumerable types of social space, some small and intimate, others grand and monumental. Large parks are extensive landscapes that are integral to the fabric of cities and metropolitan areas, providing diverse, complex, and delightfully engaging outdoor spaces for a broad range of people and constituencies.

In this collection of essays, the numerous references to well-known large parks such as London’s Hyde Park, Paris’s Bois de Boulogne, New York’s Central Park, or Amsterdam’s Bos Park capture what for many people are the ultimate virtues of such places – their full experiential range and consolidation of a public’s sense of collective identity and outdoor life. Large parks afford a rich array of social activities and interactions that help to forge community, citizenship, and belonging in dense and busy cities. Their scale (defined in this volume as being greater than 500 acres) allows for dramatic exposure to the elements, to weather, geology, open horizons, and thick vegetation, all revealed to the ambulant body in alternating sequences of prospect and refuge – distinctive places for overview and survey woven with more intimate spots of retreat and isolation. These huge experiential reserves are the great outdoor nature theaters of the city, stages for the performance of natural and cyclical time alongside the reveries of social use and event. Large parks are priceless, and those cities that do not have an effectively designed one will always be the poorer.

In addition to their experiential and cultural effects, large parks are also valued for their ecological functions. These vast tracts of land are effective at helping to store and process stormwater, to channel and cool air temperature in the urban core, and to provide habitat for a rich ecology of plant, animal, bird, aquatic, and microbial life. To use an old but still relevant analogy, large parks function as “green lungs,” cleaning, refreshing, and enriching life in the metropolis. Their large, contiguous, non-fragmented yet differentiated area is fundamental to their ecological performance, and aspects of wildness are inescapable.

These profound cultural and ecological virtues of large parks will doubtless guarantee their preservation over time and increase demand for new parks in the ever-expanding city. Today, most current large-scale urban design initiatives around the world typically link dense built development alongside or around large swaths of newly designed open space. In part, these open spaces are bargaining chips to compensate for expansive building, but they can also assume designed dimensions of enormous social and ecological value – enhancing and distinguishing the development as a whole.

This demand for large parks is also stimulated by the huge transition around the world from industrial to service economies, creating a vast inventory of large abandoned sites. These sites – old factory and production properties, closed landfills, decommissioned ports and waterfronts, former airfields, and even neighborhoods and sectors of cities where labor has migrated and left empty tracts of towns – lend themselves to being transformed into radically new forms of public parkland and amenity. Needless to say, the challenges to remediating these sites for new public uses are enormous and have led to the advancement of ecological restoration methods within the field, as well as a new regard for emergent management and cultivation techniques. Concurrently, the post-industrial aesthetic – the tough, machinic, strange quality of these sites – has produced an alternative image to the rural pastoral that has dominated public expectations of what parks should look like for the past two centuries. The time for the reinvention of large parks has never been better.

At the same time that large parks provide so much delight, space, and function, they also pose enormous challenges. While expensive to design and build, they are even more expensive over time to operate and manage. In times of fiscal cutback, parks maintenance is first to be cut, and parks can quickly fall into states of disrepair and dereliction. When this happens, parks become the city’s backyard, the venue of illicit use, violence, and dumping – the urban wilderness. Parks need stewards, involved constituents, intelligent managers, and fairly healthy budgets if they are to be effectively cultivated for future generations. They also need reinvention, for the parks of yesteryear are practically impossible to recreate.

Whereas the physical, cultural, and experiental delights of large parks are the focus and raison-d’être of their creation, the ecological, operational, and programmatic aspects are less obvious and less understood. And yet in recent years these latter concerns have become of primary importance in the production of large parks. These are specifically important landscape architectural concerns, and they are rightly the main focus of attention for the authors in this collection. Parks after all are not simply natural or found places; they are constructed, built, and cultivated – designed. As design is subject to geometrical, material, and organizational invention, large parks do not have to simulate the pastoralism of rural scenery, and neither do they have to embody the beaux-arts formality of axes and planes. Consequently, the design of large parks remains an open question, one that each designer beginning a new project must ask. Criteria of site, program, constituency, and relevant expression drawn from current ideas drive the process until the park finally takes on form, amplifying, dislocating, and juxtaposing the unique attributes of the project. And even then, given the vast scale and timelines involved, a park’s physical and spatial form will likely be subject to further revision, management, and change over time. These latter issues – design, construction, process, technique, concept, and temporality – form the basis of this book, aimed as it is primarily to landscape architects, both academic and professional. And the crux of the debate concerns the relative attention a designer must pay to fixed form versus open-ended process, or more precisely to the ratio and interaction between these two parts of the large-park equation. Added to this equation might be a third interest, of meaning and content. Along these three lines then – fixed form, open process, and meaning – the various authors stake their claims and establish their relative ratios, with some pushing for greater fixity, others for more open-endedness, and some for more (or less) meaning.

Large parks will always exceed singular narratives. They are larger than the designer’s will for authorship, they exceed over-regulation and contrivance, and they always evolve into more multifarious (and unpredictable) formations than anyone could have envisaged at the outset. They are complex, dynamic systems. As such, the designer of large parks can only ever set out a highly specified physical base from which more open-ended processes and formations take root. The intelligence of this base foundation – its geometry, material, and organizational dynamics – is the basis around which diversity, growth, and meaningful interactivity may be both instigated and supported over time. If this staged groundwork is too constrained or too complicated or too mannered, it will eventually calcify under the weight of its own construction; if it is too loose or too open or too weak, it will eventually lose any form of legibility and order. The trick is to design a large park framework that is sufficiently robust to lend structure and identify while also having sufficient pliancy and “give” to adapt to changing demands and ecologies over time.

Many successful large parks of the past succeed ingeniously in fulfilling these various equations – think of Hyde Park, Central Park, or Bois de Boulogne. What makes it much more difficult and substantially different today, however, is the process by which large parks get made. Large parks are no longer under the purview of kings or single powerful agencies. Instead, large parks today must deal with huge and multifarious constituencies, comprised of many contradictory and opposing parties, often steered by complicated and conservative bureaucracies. Issues of design, form, expression, and process are quickly subjugated by issues of stewardship, maintenance, cost, security, programming, and ad hoc populist politics. These are all important and valid concerns, and the large park designer needs to show continually how the design, form, expression, and process they are setting forth accommodates and exceeds each of these more prosaic yet inescapable issues. If a design cannot demonstrably do this, the result will be the typical bland, populist pastoral pastiche that passes for most “recreational open space” today, with none of the grandeur, theatricality, novelty, or sheer experiential power of real large parks. This is the challenge for landscape architectural design and the broader public imagination in this century, and some of the most critical parameters and strategies for rethinking such a practice are laid out in the pages that follow.

Introduction

Julia Czerniak

The special value of the Central Park to the city of New York will lie, and even now lies, in its comparable largeness.

– Frederick Law Olmsted

This book presents essays on an increasingly hard to define landscape type, the park. Two thoughts motivate our work on existing and planned parks internationally. First, initiating a study of parks selected by size cuts across conventional binary categories of classification – historic or contemporary, built or unbuilt, urban or peripheral, competition sponsored or commissioned – and enables review of landscapes not usually considered collectively. The simultaneous consideration of, say, Central Park’s circulation strategies (843 acres, 1858) and Field Operations’ organizational strategies for the Fresh Kills Landfill (2,200 acres, 2001) provides opportunities to both contextualize and advance thinking about parks, in this case looking specifically at design strategies that give them resilience.

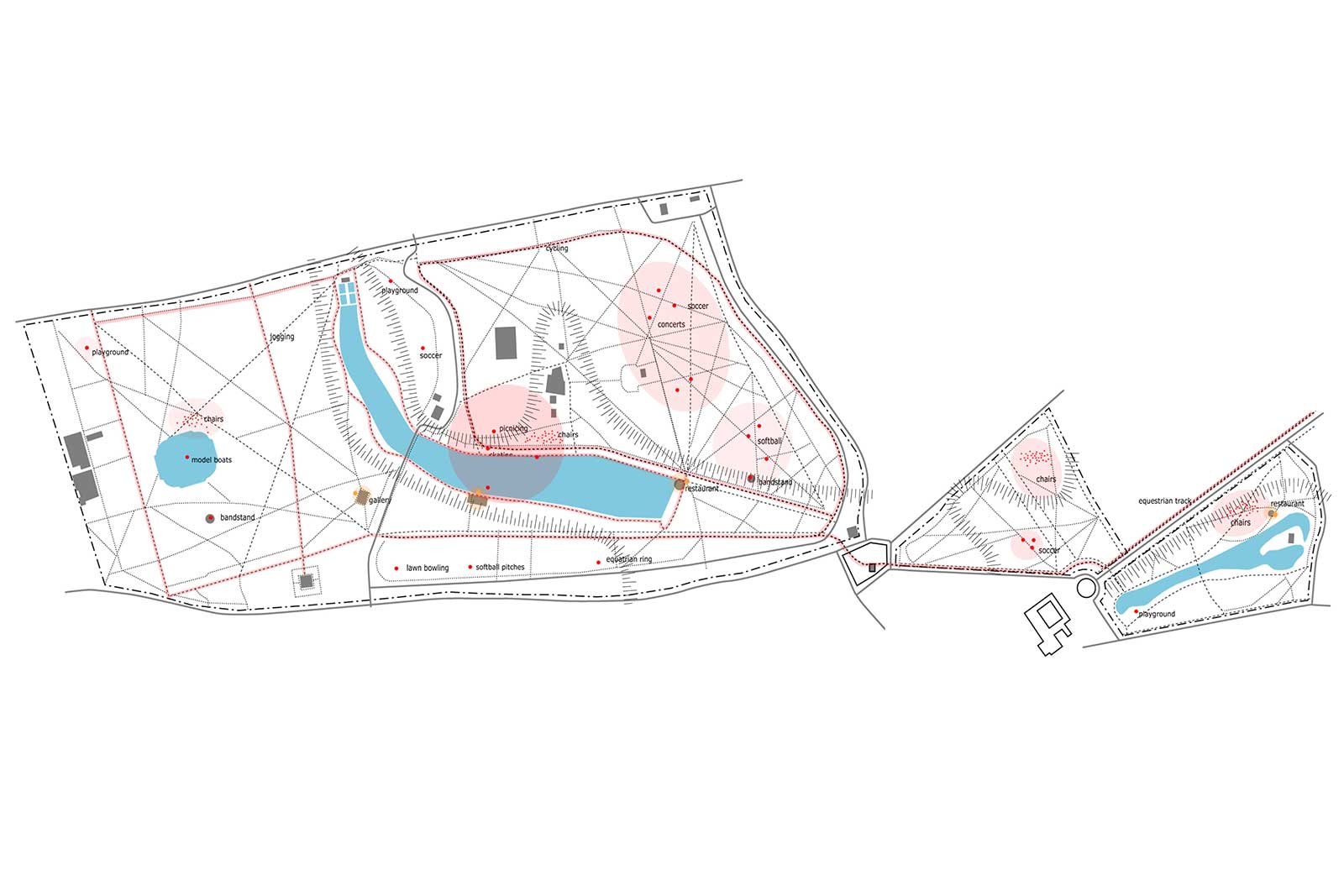

Second, the adjective “large” foregrounds a set of preoccupations in landscape discourse that relate in complex ways, such as ecology, public space, processes, place, site, and the city. Although these aspects of our environment are present in smaller parks, a large park both contains the space that promotes their full interaction and is tangent to a great diversity of urban influences. Given the number of large parks now being speculated about, designed, and planned – such as the Los Angeles River park system as reimagined by Hargreaves Associates (582 acres); the parque del río Manzanares over the M30 in Madrid (679 acres) by landscape architect West 8 and a team of architects; Lake Ontario Park in Toronto (925 acres) by James Corner/Field Operations; North Lincoln Park in Chicago (1,000 acres), envisioned by more than one hundred teams in an ideas competition, including a winning scheme by Clare Lyster, Julie Flohr, and Cecilia Benites; the Orange County Great Park in California (1,316 acres), by a team led by Ken Smith; or Ayalon Park in Tel Aviv (1,976 acres) by Latz + Partner, part of which is a reclaimed landfill – a study of large park design, management, and use is timely and necessary.